We’re often asked: “What makes something a Citizens’ Assembly”?

The short answer is that a Citizens’ Assembly needs to meet a specific set of standard deliberative principles including representativeness, time, information, influence, deliberation, and a free response.

“Is this like how champagne is only champagne if it’s from the Champagne wine region?”

No, it’s not simply when something is commissioned by a government or run by the right people that makes it a citizens’ assembly.

It is more like how Fairtrade products must meet standards related to labour practices and environmental sustainability.

The long answer is that we know that when deliberative engagement projects don’t meet these standards, they run the risk of not living up to their expectations. This creates a risk for everyone involved including those decision-makers commissioning the deliberative processes for the first time, the communities in which they’re being undertaken, and the engagement providers delivering the project.

When projects fail, they damage reputations elsewhere and they hurt communities that invest significant resources in the hope that they will help address challenging public issues. It’s important that we help support people who are enthusiastic about citizens’ assemblies and want to see them used everywhere by clearly guiding their expectations.

“What if I want to run a citizens’ assembly but can’t afford the investment?”

This comes up often. Assemblies are a significant investment and so they might not be appropriate all the time. You can still maximise your use of deliberative principles (below) without calling your project a Citizens’ Assembly, you’ll still get the benefit of those principles!

“What happens if I don’t stick to the standards?”

The standards are there to help guide people on what works best.

If you don’t recruit a representative sample of the population via a democratic lottery, people outside of the process are much less likely to trust it because someone like them may not have been included. You are also much more likely to only hear from people who are either impacted directly by a decision or have the time and resources to support their involvement.

Without enough time, people may not be able to consider the full range of views on the issue or be able to work together and find common ground on a set of recommendations. This can look and feel like the organiser is shaping the process toward a preordained outcome (even if that isn’t the case).

If people don’t receive a wide range of views or cannot request their own additional information, they will not trust that they have been allowed to properly consider the issue at hand. This can introduce biases into the process and skew the result.

Without a high level of influence on a decision, people are unlikely to consider taking the time out of their busy lives to participate in an Assembly. It’s important that people feel assured that their commitment will result in something happening. This impacts the type of people who say yes to invitations which ensures a wide range of people are involved, not just the usual suspects.

Allowing participants to freely respond to an open question and self-author their recommendation report ensures that the organiser cannot shape the process around a preferred set of outcomes. This is important for the integrity of the project but also empowers the participants to think broadly and creatively when addressing an issue.

Without the support of independent facilitation to ensure participants learn together, weigh up a range of perspectives, and consider complex trade-offs, groups of people will struggle to find agreement. That’s because deliberation is very different to debate. We use an 80% supermajority principle that ensures the recommendations put to decision-makers reflect the common ground view of the group.

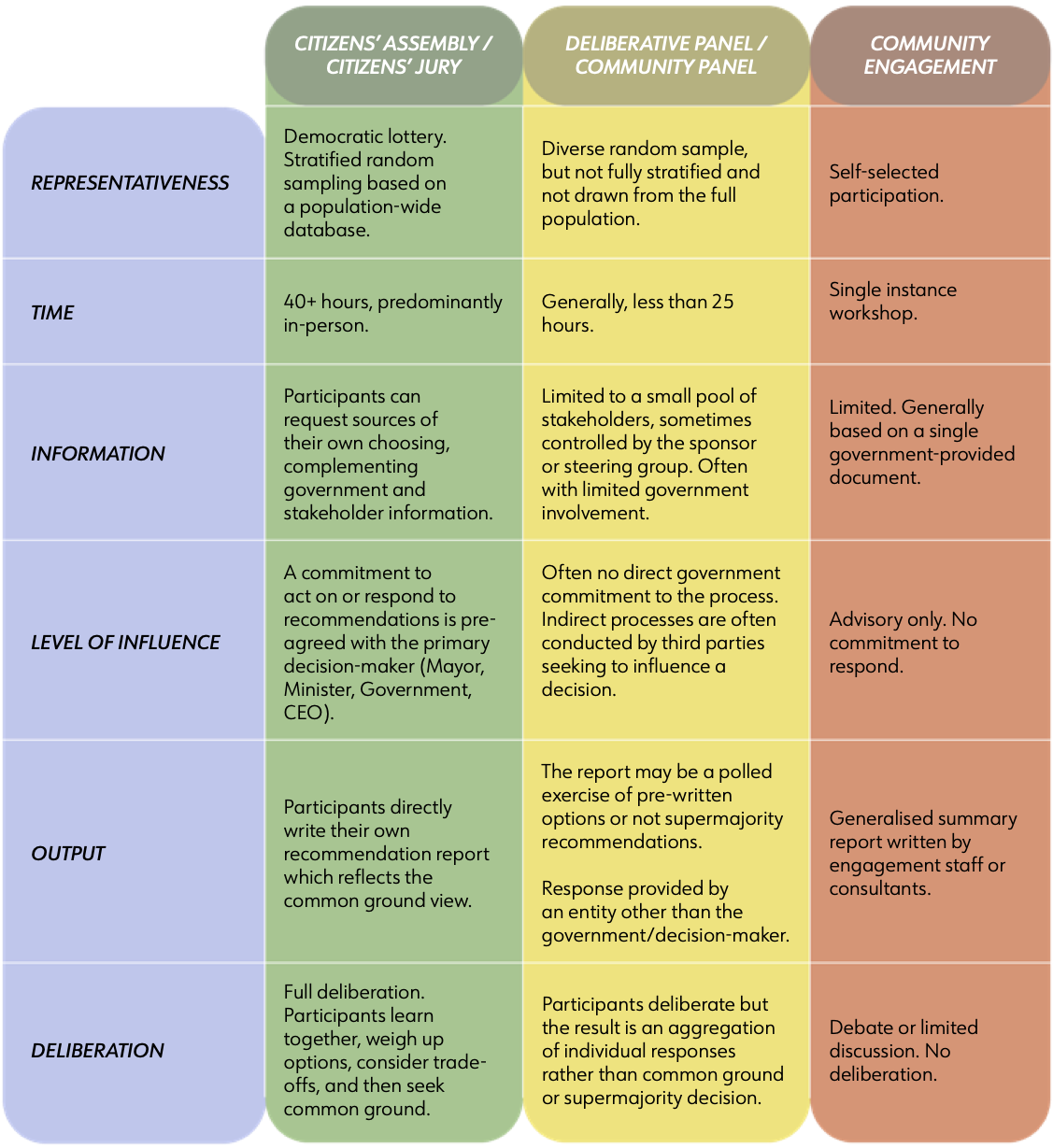

Comparing Citizens’ Assemblies and other forms of engagement

How to read the table: Hit all six squares in green and you’ve got yourself a citizens’ assembly. Dip your toes into the yellow and you should use a different name and consider what promises you’re making. Anything in the red and you’re doing community engagement that might have some deliberative elements.

Deliberative principles

It is difficult for large groups of people to find agreement on complex decisions. The OECD and the United Nations Democracy Fund recommend key principles that improve the deliberative quality of group work by creating the ideal environment for the consideration of the broadest range of sources while giving people time, an equal share of voice and influence.

1 INFLUENCE. There should be clarity on how recommendations will be acted on or responded to by the decision-maker.

2 A CLEAR REMIT. It should be clear tha you’re asking people to address a specific problem and what their scope is for making change

3 A DEMOCRATIC LOTTERY. This ensures there is a fair method for choosing people that goes beyond the usual suspects and includes everyday people from all walks of life.

4 ADEQUATE TIME. People need enough time to consider lots of information and work together to find common ground, any less and the quality of the work is at risk.

5 DIVERSE INFORMATION. There are lots of views on any given topic and people will need to consider a wide range of sources to be able to fairly justify their final recommendations, this involves people being able to request experts they trust.

6 DELIBERATION, NOT DEBATE. Group deliberation requires careful and active listening, an opportunity for everyone to speak and the consideration of multiple perspectives. This requires skilled and independent facilitation.

7 A FREE RESPONSE. A group should be able to provide their own set of recommendations with a rationale and supporting evidence that emerges from their shared learning without feeling led by the government or limited in their exploration of the issue.